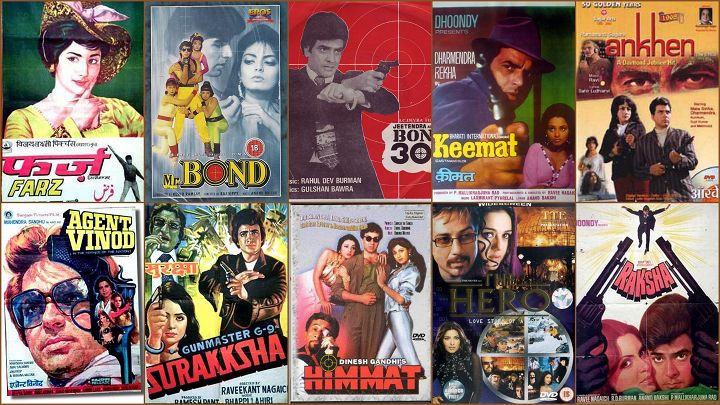

Check out something that I found online. Its more on his poetry than his songs. He has written songs for only four films Umrao Jaan, Gaman, Anjuman and Faasle. There are also some rare songs sung by Shabana Azmi herself.

‘Urdu poetry is often understood to be about little other than courtly love and romantic excess, about the lament of the bulbul and the frenzied passion of the shama‘-parvana. In Shahryar’s skillful hands, the Urdu ghazal and nazm have acquired a new potency and immediacy within their time-honored confines. The joys and sorrows of ordinary, lived experiences, the complexities and ambivalences of city life, the oppressive sense of melancholy and dislocation of the urban milieu—these and other such permutations form the rubric of his poetry.’

Rare songs from the movie Muzaffar Ali’s Anjuman. Shabana Azmi is the singer.

‘Shahryar’s songs for popular Hindi films such as Umrao Jaan, Gaman, Anjuman, and Faasle enjoy an enduring mass appeal. Taxi drivers in Mumbai are still apt to play “Seene mein jalan, aankhon mein toofan sa kyun hai / Is Shaher mein har shaks pareshan sa kyun hai” decades after the film’s release. Popular Hindi film playback singer, Asha Bhonsle, is still known to open many a concert with those haunting lines from Umrao Jaan: “Yeh kya jagah hai dosto, yeh kaun sa dayar hai / hadd-e nigah tak jahan ghubar hi ghubar hai.”

Despite early critical acclaim and commercial success, Shahryar has consistently refused to become a performer playing to the gallery at mushairas, or merely a successful wordsmith churning out hits from a plush Bollywood studio. For over thirty years now he has been straddling two worlds with consummate ease—that of academia and poetics. Honored with several prestigious national and international awards, including the Sahitya Akademi prize, Shahryar retired as Professor of Urdu from the Aligarh Muslim University. He now devotes his time entirely to his poetry, and, occasionally, to cooking exotic meals for close friends.

What sets Shahryar’s poetics apart from that of other modern Urdu poets is the sheer lyricism, the sweet melodiousness that is all the more striking because it is garbed in an everyday, conversational idiom. The relentless probing of his own heart and of the human predicament is viewed through the prism of his intensely personal experiences. At the same time, there is none of the stridency or the militant ideology of any particular school of thought which mars much of the modern poetry coming out of India, irrespective of language. Instead, there is a collage of images that tell a story of their own. Sensual, multi-colored, delicately filigreed, these word pictures—tumbling out of a kaleidoscope of the known and the familiar—capture, with just a few deftly drawn strokes, the pathos and alienation of the urban individual. Unabashedly personal, Shahryar’s nazms, such as the ones chosen here for translation, reach out to form an immediate bond, claiming a sense of kinship, touching a chord somewhere, evoking the tremulous wonder of dreams.

Dreams, in fact, are a leitmotif that runs through much of his poetry. Sleep, the ability to fall asleep effortlessly and to pass through the portal of consciousness into some magical land of dreams and into the vast, untapped subconscious are recurring concerns. So much so, that two of his collections revolve around them: Khwab ka Dar Band Hai and Neend ki Kiran. The images, too, particularly in his nazms, have a dreamy, trancelike quality evoking a mindscape that is personal yet reaches out far beyond the immediate and the individual. Reading poetry in translation has been described as an experience similar to looking at the wrong side of a carpet, for a translation can seldom match the color and sheen, the play of light and shade, the intricate word patterns of the original. Retaining the compactness and metaphoric precision of Shahryar’s na ms while also carrying into English some of the rhythm and rhyme of the poet’s own often idiosyncratic use of words and silences can be quite daunting. Unlike English, metrical patterns in Urdu depend on line lengths and lengths of syllables rather than stresses. There is also no preordained word order, and punctuation is seldom used, the poet preferring to allow natural pauses to do the job. Frog-marching the rhythm of the nazm into English results in ungainly, dangling sentences. And nothing can be more tiresome than a clumsy jumble of words being passed off as poetry in translation. I have found it best, therefore, to stay as close to the images as possible and let them carry the poem through where rhythm and rhyme have proved elusive.’

Tags: Anjuman Gaman Muzaffar Ali Rekha Shabana Azmi Shahryar Suresh Wadkar Umrao Jaan

All songs in Umrao Jaan are Brilliant but i don’t know why he has done 4 films.